Dr. Margus Ott (Tallinn University) interviewied Dr. Rogacz about Chinese philosophy and translated the interview into Estonian for the cultural magazine “Sirp”. Other interviewees include Prof. Jana Rošker (University of Ljubljana) and Prof. Ady Van den Stock (Ghent University). Interview is available here.

For those who do not read Estonian, the English version attached below:

1. What brought you to Chinese philosophy?

As a person who had known the main currents of the Western philosophy already in high school, I was more than intrigued while encountering Asian traditions of thought during the first year of my philosophy studies. Paradoxically, it was internal diversity of the Chinese thought that I was enchanted with. I was digging into classical and less classical sources, realizing that despite popular associations, Chinese tradition has given life to many forms of individualism; that in addition to ethics and political philosophy, which occupy a central place within this intellectual tradition, metaphysics and theory of knowledge were no less important to the minds of premodern Chinese. I was digging so much that I finally decided to start studying Sinology, at the same time finishing the philosophy studies. I had read Confucius’ Analects and the Daodejing before any other Chinese text. For many colleagues of mine, I was just another weirdo, because no one in their right mind learns Chinese in order to read some texts that were written on bamboo slips two thousand years ago. In Poland, as in many other countries in the world, Chinese studies are treated as a promising yet demanding trampoline for young, linguistically skillful students who want to respond to the new world order in the most timely manner. In this sense, I was deliberately untimely. It does not mean that Chinese philosophy has no impact upon the course of history and the shape of Chinese (and thereby also world) culture – it is quite opposite. But even then, as a purebred philosopher, I always tried to deduct the current situation from something more general. In this sense, I always believed that Chinese philosophy is essentially universalistic in its message. As Karl Jaspers expressed it from the perspective of a Western reader, “the history of Chinese and Indian philosophy is no mere superfluous repetition of our own, nor is it simply a reality in which we can study interesting sociological effects. On the contrary, it is something that directly concerns us because it appraises us of human potentialities that we have not realized and brings us into rapport with the authentic origin of another humanity”.

2. What do you consider to be some of the major contributions of the Chinese tradition to the world philosophy?

I would say that it is the very idea of the world philosophy. Throughout the ages, the Chinese tradition has shown a magnificent ability to accept and absorb other traditions (despite its Sinocentrism!). Already at the turn of what Europeans call “eras,” Buddhism along with its philosophical tradition came to China. The Chinese not only sinicized the Indian schools of thought, but also created their own traditions, such as chan (later zen), and transmitted them to the Japanese. After Jesuits came to China, some Chinese intellectuals became familiarized with Christian philosophy. Imagine that in 1631 Aristotle’s Categories were translated into Chinese and commented by Chinese neophytes! Due to the fruitful, and let’s stress it, two-sided co-operation, also Europe became acquainted with Chinese thought, which turned out to revolutionize its worldview, since Chinese chronology directly contradicted the Biblical one and the Chinese ethics stood in stark opposition to the thesis that one cannot be moral without being a Christian (some serious problems that were at the center of debates of such thinkers as Leibniz, Voltaire, and Herder). In the nineteenth century, Chinese thinkers responded to such philosophical systems as evolutionism, Hegelianism, Marxism, and positivism, and in the twentieth century, they developed many intriguing concepts in almost every field of philosophical reflection, from ontology, logics, aesthetics, to the philosophy of culture. In his book on the interactions between twentieth-century German and Chinese thought, Eric Nelson demonstrates that European philosophers, Heidegger and Buber included, were also aware of the main contributions of Chinese philosophy. I believe that the example of Chinese thought shows us how to dialogue with other traditions without looking down on anybody, and finally – how to make a world philosophy that is actually something more than a patchwork, or a loose comparison of differences lacking any real hope for building something together.

3. I know that you are about to publish a book based on your PhD dissertation, on the topic of Chinese philosophy of history. Could you bring out some most interesting findings?

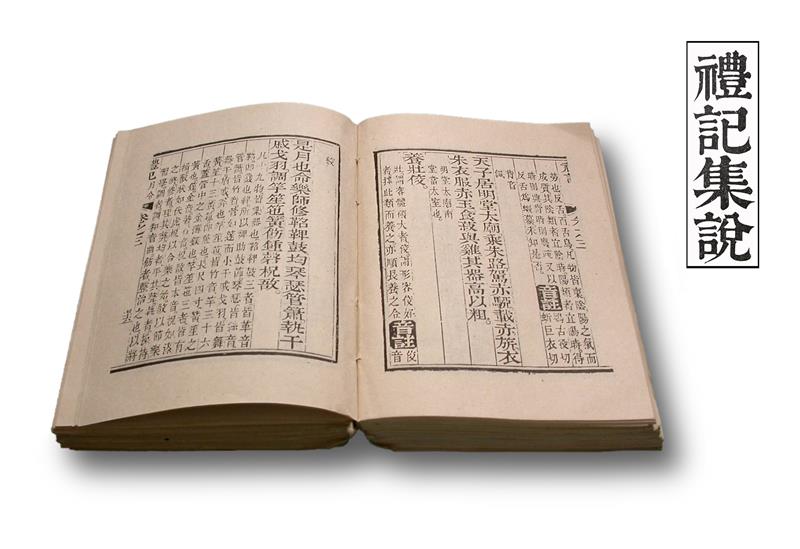

Yes, the book is entitled Chinese Philosophy of History. From the Ancient Confucianism to the End of the Eighteenth Century and it is a first monograph in any Western language devoted to a comprehensive treatment of the classical Chinese philosophy of history. It may be said that the book challenges the popular misconception that the philosophy of history is a specifically Western invention, namely the result of the secularization of Christian eschatology (as claimed by, i.a., one of Heidegger’s influential disciples, Karl Löwith). The book presents a meticulous analysis of the philosophical views of history and historical writing created by more than forty Chinese philosophers of history, many of whom are virtually unknown. Because of ‘inherited’ gaps in the terminology, when the Western conceptual apparatus does not have an appropriate term that reflects the essence of a given Chinese concept, new terms, such as “historical populism,” “prospectivism,” or “speculative philosophy of historiography,” are introduced. Accordingly, also the scope of meaning of existing concepts, such as “historical materialism” (which is treated almost as synonymous with Marx’s position), have been extended. In other words, based on concrete examples of premodern Chinese thinkers, I argue that historical materialism understood as a philosophical position was represented long before Marx, and was developed in more than one, namely economical, way. For this reason, the book not only entails debates on the interpretations of particular philosophers of history, but also tries to provoke further discussion on the meaning of these basic philosophical categories. In fact, I hope that my findings will annoy some of the Eurocentric historians of philosophy to the extent that they will devote their valuable time to discuss these Chinese cases, and thereby bring these unfairly forgotten thinkers to light, making them knowable to a broader intellectual audience.